The use of Python on Jupiter-labs was an essential tool to compare and analyze the differents lists of words contained in the dictionaries.

The code was useful to do some of the tasks required to analyze the different corpora. For instance, separating the entries from their definition, analizing the presence or absence of words in the princeps and the second edition, and establishing the coincidences between both dictionaries.

The following two notebooks might help you to understand the process. Click on their titles if you want to download them.

Inside Nebrija's dictionaries we can witness an evolutive process towards modernity. The most important characteristic is, according to Alvar Ezquerra (1988), the removal of all all medieval and encyclopedic ornamentation from his definition. This meant the capacity to reduce the dictionary to a tool that offers a short text for each entry, and at the same time allowed increasing the number of entries. Nebrija managed to avoid almost completely the use of more than one line when providing the equivalents for each of the lemmas in both dictionaries, the Lexicon and the Vocabulario.

If the two princeps editions (from 1492 and 1494) are compared, the elimination of certain proper names from one edition to another displays the step from a classic tradition to a modern one.

As it can be seen in the graphic, the most used words responded to the reductionist formula "por cosa...", "por aquello..." "por lo mesmo...", etc.

In the search of evidence to understand the differences between the first and the second edition of the Vocabulario, we came across an important finding related to the application of Nebrija's principles when composing the matrix to print his works. Among his description we can find one of the most important features that would shape modern Spanish language: “tenemos de escrivir como pronunciamos y pronunciar como escrivimos” (we have to write as we pronounce [words], and pronounce as we write).

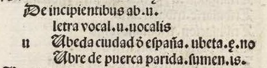

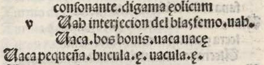

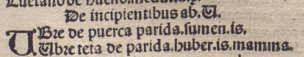

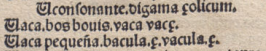

In the princeps editions, printed in Salamanca in 1492 and 1494, the author's will seems to be more present than in the following editions of the dictionaries. Proof of this statement can be found in the variations of orthography or spelling used in both editions. In the first editions there is a well defined, if not completely standardised, use of the letter 'u' and 'v' according to the principles established by Nebrija in his Gramatica Castellana.

While in the second editions, and their further copies, the graphic representations of the sound /u/ as a vowel and as a consonant are swapped.

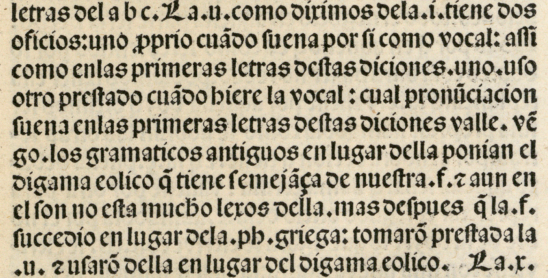

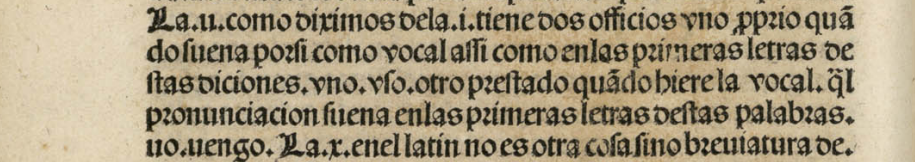

Other features that could be remarked during the project were the variations in the typeset used for printing Nebrija's works out of Salamanca and the way in which the tradition of each editor affected the principles proposed by the author. On the one hand, we found that an important part of the text presented in the Grammatica Castellana (1492) to define the use of some sounds and letters, such as /u/, was reused for printing the Reglas de orthographia (1517). On the other hand, we have a printed text whose orthography is not coherent with what it reads. These issues can be seen in the following extracts:

If we observe carefully the text in Reglas de orthographia (on the right), printed in Alcala at Arnao Guillen de Brocar’s workshop, and compare it with the text in Grammatica castellana (on the left), printed in Salamanca by Juan de Porras, we can notice that the use of round and the angular shapes for the sound /u/ in Reglas de orthographia does not match what is established in the rules for their use.

The project provided several examples where typographical decisions and mistakes led us to be more inclined to believe that Antonio de Nebrija, as the first person who set the first grammar and lexicographic rules for the vernacular language destined to become the language of an empire, tried to reinforce the use of his principles in his own work. Nebrija knew the importance of establishing well-defined rules between Castilian and Latin to create a linguistic identity. Therefore, one of the conclusions of the project is to question the use of the second edition of the Vocabulario as the base text for the creation of the critical edition due to the orthography it uses with respect to the use of the U and the V.

After comparing the list of words of the littera B of the Lexico and the letter B of the Vocabulario in the princeps edition and the copy of the second edition printed in 1516, the results were not coherent to what was expected if the information of the colophons used in later editions was taken into account. It was necessary to do the inventory of other letters (u, x, z) to verify if there was a pattern in the ratio of deletions.

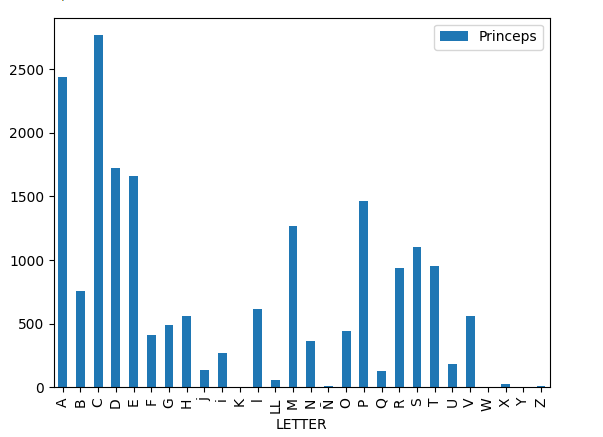

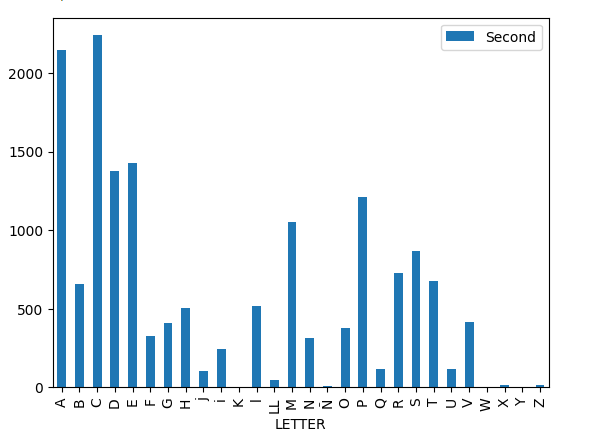

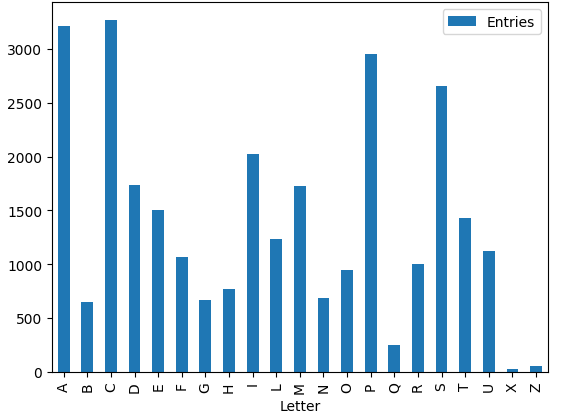

At this point of the analysis, it was decided to count the entries for each letter of the alphabet in both editions of the Vocabulario to have an overview of the proportions occupied by each set of words in the dictionary. The results are displayed in the following graph.

After this project, the use of round numbers when refering the total of entries in each dictionary can be dropped. Thanks to the combined work of AI and ground-truth, it can be affirmed that the Vocabulario of 1494 contains a total of 19.358 entries, while its second edition contains 15.940.

Concerning the Dictionario latino hispano, it is necessary to define the number of total entries in 28.989.

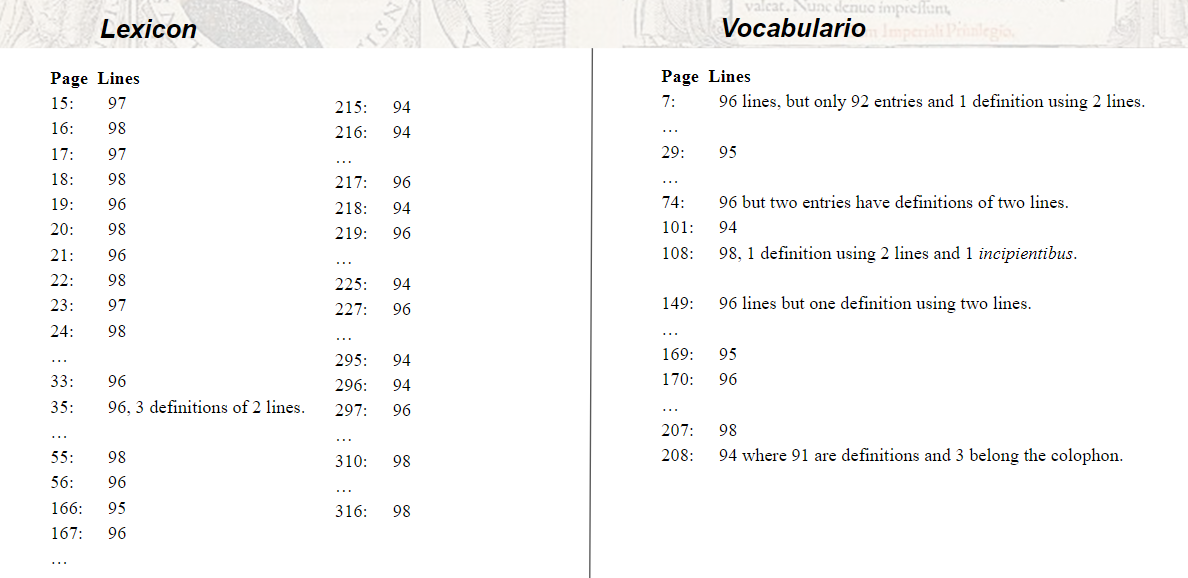

Perhaps one of the main reasons that affected the counting of lemmas in both dictionaries was the lack of pagination. By not having their pages numbered, the most practical method to count the lemmas was having the number of pages multiplied by the number of entries, given in two columns, per page. Thanks to the use of the AI assisted transcriptions, we were able to prove wrong this method so commonly used by some scholars.

We offer a diagram where we can see the actual variations in the format of two columns of 49 and 48 lines per page, resulting in 98 or 96 lemmas in almost every page depending on the dictionary. The Lexicon tends to have 98 entries per page, while the Vocabulario has 96. The following diagram displays the pages where the format is modified: